Sarah Yatsko of the University of Washington’s Center on Reinventing Public Education says schools have it all wrong when it comes to meting out suspensions and expulsions.

She offers up six supposed myths associated with suspensions and expulsions which supposedly are out there being discussed (although after twenty-five in public education, I don’t recall ever … “wondering” about any of these, save perhaps number three), and then like any good researcher proceeds to “debunk” each of them to back up her point-of-view.

To begin with, if you want to make a teacher roll his/her eyes, start a statement with “The research shows …” Considering the multitude of edu-fads with which teachers have had to put up over the last few decades, the question then becomes “When will the ‘research’ actually get it right?”

Myth 1: It’s rare that a child is suspended or expelled.

Last year, Washington schools levied more than 68,000 suspensions and expulsions, according to the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). Rates peaked at the end of middle school, with nearly one out of every 10 eighth graders suspended or expelled. One out of every 65 all-day kindergarteners was also excluded from school for behavior.

According to Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), there were 1,055,517 students enrolled across Washington State (in 295 districts) as of May 2014. With roughly 68,000 suspensions/expulsions (expulsions are a much rarer occurrence), this means approximately six percent of students were suspended.

Or does it? Ms. Yatsko does not say how many of those 68,000 suspensions include repeat offenders. Since a great many students who end up getting suspended are repeaters, it’s highly likely the actual number of students suspended is less than six percent.

Myth 2: Most students are suspended or expelled because they’re dangerous.

Aside from fights — which made up 15 percent of suspensions and expulsions — only 7 percent of all reported suspensions and expulsions in Washington in 2013 and 2014 were for violence, according to OSPI data. More than half of all suspensions and expulsions fall in the discretionary “other behavior” category, which does not include alcohol, bullying, drugs, fighting or violence.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard a teacher state this “myth,” let alone believe it. That being said, what about a student screaming “F*** YOU!” to a teacher in the middle of class (a class of 30-plus kids, mind you)? Over and over? That behavior doesn’t doesn’t fall into the categories listed. Why would this not be an offense worthy of suspension … especially if it is a repeated behavior?

Myth 3: Suspending and expelling students keep schools safer and improve learning.

High suspension and expulsion rates can actually make schools less safe. Students — including the ones causing no trouble — experience overly punitive discipline practices as unfair and alienating. Several studies have documented how students in these schools are less likely to trust adults and thus less likely to share critical information with them that could help prevent incidents of acting out or violence. Findings from a study at Indiana University take this further and suggest that high levels of exclusionary discipline can negatively affect the academic achievement of non-suspended students.

This is the best proof that Ms. Yatsko has never taught a day in a public school. Note the use of her words “can” and “suggest.” Also note the wording of the second study:

An influential literature in criminology has identified indirect “collateral consequences” of mass imprisonment. We extend this criminological perspective to the context of the U.S. education system, conceptualizing exclusionary discipline practices (i.e., out-of-school suspension) as a manifestation of intensified social control in schools.

Emphasis added. It goes on to state the research “level[s] a strong argument” against “excessively punitive” discipline measures and argues for policies that establish a “disciplined environment through social integration.”

*Sigh*

You’ll hear no better rationale for the growth of private, parochial, charter, and home schooling than that which says getting rid of constantly disruptive and dangerous kids from an educational environment is a bad idea. Not to mention, ask students who come to school wanting to learn — you know, the actual purpose of a school, after all — if they think getting rid of constantly disruptive and dangerous kids from their classrooms is a bad idea … and if such an action actually harms them.

If this is isn’t common sense enough, there are studies out there which prove it. Rochester University’s Joshua Kinsler’s study published in International Economics Review found that “cutting out-of-school suspensions in schools with many disruptive students lowers overall student achievement.”

Myth 4: Suspensions and expulsions teach kids a lesson.

Rather than preventing misbehavior, suspension and expulsion can reinforce it. A 2011 Texas study found suspensions and expulsions increased a child’s likelihood of being disciplined again, being held back a grade, dropping out or getting involved in the juvenile justice system — even when you hold many other factors constant.

So, teachers and school officials should avoid disciplinary measures such as suspension … out of concern that a kid may face discipline again?

Again, suspensions are more for removing a chronically disruptive student from the learning environment so that — go figure — everyone else can learn. Expulsions, much more rare, are utilized only for major infractions such as fighting which severely injures another student, an attack on a teacher or administrator, or drug/weapons violations.

Myth 5: Whether or not a child is suspended or expelled depends entirely on his or her behavior.

The Texas study describes school discipline as “multiply determined” by many factors. For example, a black student is three times more likely to be suspended or expelled than his or her white peer — even when the two are identical in every measurable way (including type of offense, discipline history and poverty level). Being a boy, in special education, or identifying as gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, transgender or queer all increase a student’s odds of being suspended or expelled. Moreover, out-of-school discipline rates vary widely from school to school and teacher to teacher, even when demographics match. In 2013 and 2014, the range among districts in Washington state was zero to 19 percent of children suspended or expelled.

Let’s examine this: A school district with which I am familiar had a legal issue with regards to racial disparities in discipline. It was accused of disciplining more black students than white, “even when the two are identical in every measurable way.” (Ironically, this is a district with a great many black administrators.)

Yet, consider “type of offense.” There are many degrees of various offenses, so that a “class disruption” could range from mere burping in class to yelling out profanity. Which is more severe? Even fighting has degrees of severity, from a premeditated unprovoked attack, to jumping into a fight to protect the victim. Which is more severe?

Should teachers and administrators not have the ability to make such judgments? Ironically, “zero tolerance” policies were put in place in response to accusations of (racial) bias in meting out school discipline — in other words, allowing teachers/administrators to make qualified judgments.

How do people feel about “zero tolerance” rules today?

Further, “being a boy, in special education, or identifying as gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, transgender or queer” alone do not increase one’s chances of being suspended. It’s not a vacuum. Boys and those in special ed classes tend to be more disruptive, period. Gay students are not; their suspensions may have to do with “educational environment” which teachers and administrators may find disrupted due to styles of dress, etc. Certainly, this is a lot more debatable regarding suspensions than actual disruptive behavior.

As for varying discipline rates, I do not know of any district where teachers have the power to suspend students. Typically, only administrators have that power.

But more to the point: The implication here is that teachers (and administrators) should not be permitted to set their own classroom/school rules. Everyone has to be “on the same wavelength,” so to speak. Teacher A may send a kid out of class for profanity, while teacher B looks the other way. Which will be on better terms with administration? Hint: Which teacher will make “the numbers look good?”

Myth 6 simply says “We don’t know how to reduce suspensions and expulsions.” Again, no teacher or administrator I know considers this a myth — because alternatives to the two (but especially the former) have been in place and utilized for decades. In-school suspension. Alternative to Suspension programs. Counseling sessions.

Such programs allow students to remain in an educational environment doing (supervised) school work, so hopefully they won’t fall behind in their classes (if, that is, such is actually important to the students in question in the first place).

I certainly agree that out-of-school suspension should be used as a last resort disciplinary consequence, and only for severe and/or repeat offenses. But more concern for those who would routinely ruin schooling for the (well-behaved) vast majority is a quite fatuous notion, and betrays those who serve “in the trenches” on a daily basis in our public schools.

Dave Huber is an assistant editor of The College Fix. (@ColossusRhodey)

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

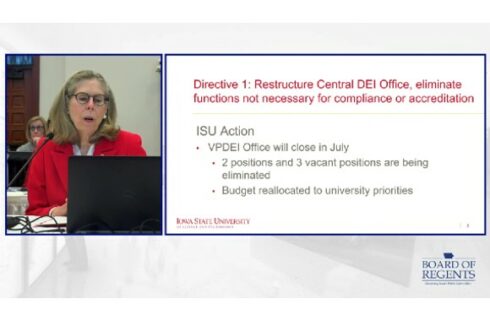

IMAGE: YouTube screencap

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.