‘We will restore the value of liberal education if we are willing to fight for it. It’s not an easy battle, but it’s also an inspiring one once you know how very valuable our heritage is.’

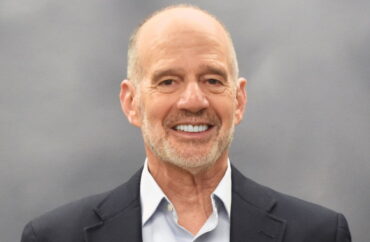

Historian Barry Strauss, a 2025 Bradley Prize recipient and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, passionately advocates for the revival of a classically liberal education.

He argues that restoring the principles of free thought, grounded in the great debates of Western civilization, is essential to empowering today’s college students to think independently, defend constitutional liberty, and preserve the values of a free society.

Strauss is a renowned expert on military leadership of the ancient world and author of 10 books on ancient history, which have been translated into 20 languages.

The prize is awarded to individuals like Strauss “whose extraordinary work exemplifies the Foundation’s mission to restore, strengthen, and protect the principles and institutions of American exceptionalism and honors the ideals of the Western tradition,” according to the Bradley Foundation.

In an interview with The College Fix this month, Strauss discussed the fall of academic ideals, the lessons of history, and his hope for the future.

The College Fix: In your acceptance speech for the Bradley Prize, you mentioned that American universities are a “tarnished treasure.” Can you elaborate more on what you have seen in higher education that prompted you to say this, particularly regarding a shift from nationalism to globalism and from liberal education to careerism?

Strauss: There are still students, faculty, and administrators who continue to value a liberal education but, from what I have seen in higher education, we need a lot more of them. Many students today are in college to build a career, not to search for truth. Both positive and negative pressures push them in that direction. On the one hand, the high cost of university and the challenges of a job market characterized by greater competition and by shrinking opportunities make students (and parents) prioritize career education. On the other hand, why study liberal education when the message of so much of it is (a) America is bad, (b) the so-called classics are a fraud, and (c) there is no such thing as truth but merely power? Or when curricula have replaced citizenship in a nation with a fuzzy notion of global citizenship? The purpose of liberal education is to empower students to make their own decisions about the big issues of life; the way to do that is to introduce them to the great debates of Western civilization, but that is too rarely on offer. Nor do enough universities prioritize liberal education.

CF: Despite your critique, you offered a hopeful vision for reforming universities from within. What practical steps do you believe faculty and administrators can take to restore liberal education and promote a more balanced environment?

Strauss: We are in an exciting period of reform and rebuilding. On reflection, however, I think that reforming universities will take work both on the inside and from the outside. It’s a “both/and” rather than an “either/or” process. Within the institution, we need leadership from administrators who understand the problem and are committed to restoring liberal education. Trustees and overseers need to back them up. Those administrators need to find like-minded faculty members and work with them. They also must be committed to devoting resources to hiring new faculty, because rare is the institution that already has enough faculty who are dedicated to those goals and not to activism instead. Finally, everyone would do well to read Machiavelli, “The Prince,” and to reflect on its lessons.

CF: As the founder and director of Cornell’s Program on Freedom and Free Societies, how do you approach teaching students about constitutional liberty, and what lessons from history do you find most relevant to today’s challenges to freedom?

Strauss: As an expert in ancient history, I teach students about the roots of constitutional government and democracy in ancient Greece and Rome. I explain how those ancient ideas influenced the American Founders and how they still influence us today. Students also need to be reminded of President Ronald Reagan’s words: “Freedom is a fragile thing and it’s never more than one generation away from extinction.” Young people take for granted the freedoms that we enjoy as Americans. The media, whether mainstream or social media, mostly subject them to a message of having fun, following the leader, and paying little attention to the lessons of history. They don’t seem to be aware that freedom must be defended or it will be lost. They don’t remember Soviet communism or the Cold War, as my generation does, and they rarely face the harsh reality of Chinese communism. It is our job to educate them, to introduce them to history, and to empower them to think for themselves. Of course, it’s up to the students to make their own choices, but at least we can present them with alternatives.

CF: Have you faced challenges for advocating free speech? If so, how have those experiences shaped your perspective on the state of academia?

Strauss: Other than fundraising or having to hire security for events with certain speakers, I haven’t faced any real challenges advocating for free speech. Of course, it’s appalling that anyone would have to hire security for a talk on a college campus, but that’s a sign of how far we’ve fallen from the idea of a university that privileges education over protest.

CF: In your view, how can the study of ancient civilizations help address the current polarization in American society, particularly when campus activists challenge the value of Western civilization?

Strauss: Western civilization has always questioned its own value. It goes back to fifth-century BC Athens, the “Golden Age of Greece.” In history’s first era of democracy, a group of intellectuals called the Sophists questioned the value of democracy or indeed, the possibility of truth. And it goes back to the Hebrew Bible, when the Israelites repeatedly doubted Moses and questioned why he had led them into the perils of the desert when they had experienced secure lives in Egypt, even if they were slaves there. So, when students hear campus activists challenge the value of Western civilization, they should respond that it is only Western civilization that allows those activists the luxury of issuing a challenge. Students should know that the very challenge proves the value of Western civilization and so they should value it all the more.

CF: Your Program on Freedom and Free Societies at Cornell investigates threats to constitutional liberty. What do you see as the biggest threat to our constitutional rights right now?

Strauss: In my opinion, the biggest threat to our constitutional rights right now is ignorance: ignorance of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, of what they say, what they stand for, and what they have meant historically and mean today. Our society has failed to provide young people with the education that they need to be citizens.

CF: Looking ahead, what is your vision for the future of liberal education?

Strauss: We will restore the value of liberal education if we are willing to fight for it. It’s not an easy battle, but it’s also an inspiring one once you know how very valuable our heritage is. Fortunately, none of us is alone, and more and more people are answering the call and joining the fight. I’m optimistic about the future.

MORE: Academic prize combats liberal bias in higher ed by supporting conservative scholars

IMAGE CAPTION & CREDIT: Barry Strauss / courtesy photo

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.