‘I would rather see Notre Dame die than be educationally mediocre’

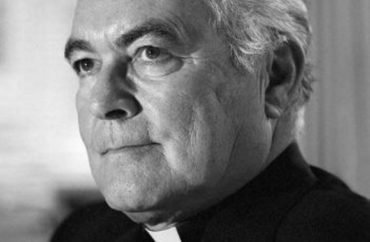

Father Ted Hesburgh — a giant of Catholic higher education — left a larger-than-life legacy that still resounds at the University of Notre Dame today.

So said panelists at an event honoring Hesburgh. They noted one of the nation’s most premiere Catholic institutions would not be what it is today if not for the efforts of a man who, above all else, prioritized excellence.

And as a book from a fellow priest indicates, Hesburgh’s passion for academia is difficult to pigeonhole into one specific political outlook.

Rev. Wilson D. Miscamble’s “American Priest: The ambitious life and conflicted legacy of Notre Dame’s Father Ted Hesburgh” is a biographical look at Hesburgh’s life. At a First Things event in New York City on Tuesday, Miscamble, a member of the history department at Notre Dame, joined editor R.R. Reno in a conversation about the book and Hesburgh’s complicated legacy.

The early parts of Hesburgh’s life were defined by speed. Born in 1917, Hesburgh grew up in Syracuse, New York, and entered into the seminary at Notre Dame in 1934. Soon afterwards, he was sent to Rome to continue his studies, before being forced to return home in 1940 as World War II broke out.

Miscamble remarked on how quickly Hesburgh was able to climb the ladder at Notre Dame as well: he became an assistant professor in the theology department in 1945; chair of the department in 1948; then in 1949, executive vice president of the university, a newly created position by John Cavanaugh, then-president at the time. And in 1952, he became president of the university at the young age of 35, a position he would hold until he was 70.

“It was a six-year term as president, and he ended up staying for 35 years,” Miscamble said.

What defined Hesburgh’s time as president was his visionary nature and his basic faith in the ability of individuals to bond together and solve problems.

“He is a classic American figure for that period,” Miscamble said. “He loves the United States deeply, and sees this post-war role for the United States as being the world leader, and he sees that Notre Dame needs to contribute in that role.”

“He believed deeply that if you got the right group of people together, and they worked, they could come up with a solution to just about any problem.”

Hesburgh ascended to the presidency at just the right time, as Catholicism was experiencing a surge up until the late 1960s, signified partially by the election of John F. Kennedy, the nation’s first Catholic president.

“It is a classic time for the Catholic Church, it’s the 1950s, families are growing, it’s good times, Catholics benefited so much from the GI Bill … there’s no question about expansion at these institutions,” Miscamble said.

Hesburgh saw the wave of Catholicism as an opportunity to build Notre Dame’s financial prowess.

“He looked at the landscape of American higher education and saw that the elite schools were the ones with the biggest endowments … he thought correlation and causation were pretty closely connected as he looked at what money could purchase, and his plans for Notre Dame grew out of the awareness of what was going on in other places,” Miscamble said.

It was not long before he began experiencing trouble, though. One section of the book details his most challenging time as president, between 1968 and 1970 at the height of student activism.

The book explains that Hesburgh attempted to keep a steady hand on order on campus, trying to be a voice of reason even as the country became engulfed in conflict following the Tet Offensive and Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April 1968, followed by Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination in June of that year.

“Father Ted had maintained a fairly careful order on campus, and in some ways had been tough on students who were wanting a sort of liberalizing of the student rules,” Miscamble said. “In fact, he once wrote to a student, ‘If you don’t like it here, you can go elsewhere’ … he’s not making easy concessions.”

“Universities are to be places of discourse and respect, was his view.”

Part of Hesburgh’s approach to dealing with student activism involved instituting what became known as the “15 minute rule.” He wanted to avoid what happened at Columbia, when President Grayson Kirk’s office was occupied and looted by a group of student protesters.

If students were sitting in and protesting, they had 15 minutes to talk to administrators and make their point. Afterwards, they had to leave. Otherwise, the school would suspend them.

This was not meant as an appeal to more authoritarian instincts, however. Miscamble said that Hesburgh was embarrassed when President Richard Nixon began elevating him up as the “paragon for how a university president should operate as compared to all those wimps in the Ivy League colleges.”

Hesburgh wanted to be identified with those “wimps,” and he ended up backtracking a little from his initial position. He spoke to thousands of students urging them to avoid violence and to channel their anger and protest in constructive ways.

Miscamble wrapped up by discussing Hesburgh’s legacy as a great institution builder.

“He was always good on means, but not good on ends,” he remarked, saying that Hesburgh had issues with delegating responsibilities.

He also became extremely spread out in his public commitments, racking up an impressive number of appointments and honors.

One audience member asked Miscamble how Hesburgh would feel about political correctness on campus today, to which Hesburgh responded that he probably would not approve of the covering up of a mural of Christopher Columbus. Notre Dame recently decided to cover its murals on campus of the Italian explorer.

Hesburgh’s legacy is one of expansion and nuance as he navigated through 35 years of his presidency. “I would rather see Notre Dame die than be educationally mediocre,” one powerful quote of his from the book reads.

His impacts on the school lives on, and Miscamble also noted his appreciation for Hesburgh’s impact on his own life.

MORE: Notre Dame theology course changes hearts and minds

IMAGE: American Priest, Crown Publishing Group

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.