Debate on race at UCLA between Jason Riley and Randall Kennedy tackles where to lay the blame for the ‘black body count’

LOS ANGELES – Two black intellectuals engaged in a heated exchange at UCLA this week over the high homicide rate among young black men and the shooting deaths of black men by racist or lawless police officers, with one arguing that’s not the main problem facing the black community and the other suggesting it’s a huge crisis.

The dispute took place during a debate on campus titled “Liberal Policies Make it Harder for Black Americans to Succeed” between Jason Riley of the Wall Street Journal and Harvard law school Professor Randall Kennedy.

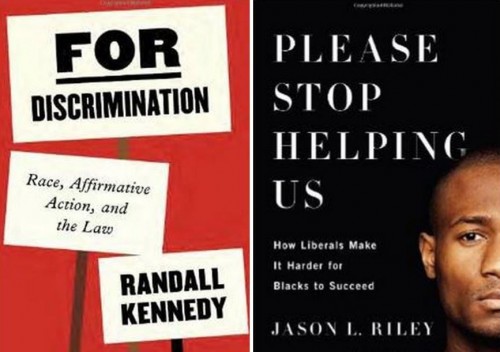

Riley is a noted conservative television and newspaper pundit who has written extensively on racial issues, including in his recent book “Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make it Harder for Blacks to Succeed.” Kennedy teaches contracts, criminal law, and the regulation of race relations at Harvard Law School. He has likewise written voluminously on race and his most recent book is “For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law.”

The testy exchange during the debate saw both speakers interrupting each other and raising their voices.

Kennedy contended that racism within police departments is a major problem that leads to the killing of blacks as well as a black distrust of law enforcement and disrespect for the rule of law. He decried “rogue cops,” and suggested the criminal justice system is unable to discipline them.

But Riley pointed out the criminal justice system is “run by one black man who reports to another black man.” He also noted that less than 2 percent of black shooting deaths are at the hands of police officers and that, in fact, 90 percent of black shooting deaths are at the hands of other blacks. He also talked about how some of the worst black crime rates can be found in cities that have historically had many black mayors and police chiefs.

“I don’t think racism is the explanation,” Riley said. “It is not the Klan driving through the neighborhood shooting it up. These black kids in Boston, New Orleans, Chicago and New York are not shooting each other because of white racism. They are shooting each other because they have no sense of what it means to be a man, or to be black for that matter. They have a warped sense of racial identity, and this is how they settle their scores. It does not have to do with white racism and cops, it has to do with upbringing and values in fatherless homes.”

Riley tied his statements in the exchange into his basic point that blacks need to stop blaming the white bogeyman and instead honestly face their own cultural problems.

Kennedy said police – the guardians of law and order – should be held to higher standards than “thugs” who commit crimes.

Riley then noted that homicide is the leading cause of death among young black men, and asked Kennedy whether focusing on police shootings of blacks or blacks shooting of blacks would help reduce the “black body count.”

“That is a huge problem that is going to require a multi-focus,” Kennedy responded. “… I am not saying white racism is the all- purpose explanation for what we are talking about. I am saying is what we are going to have to do is address many different things. One of those things, however, is the problem of police.”

purpose explanation for what we are talking about. I am saying is what we are going to have to do is address many different things. One of those things, however, is the problem of police.”

Kennedy argued that while the notion of obeying the law has broken down in some black communities because of some of the reasons Riley stated, he added another reason is “when you see the police acting in a lawless way, that too breaks down the feeling of law-abidingness.”

“There just aren’t enough of those cases to make a dent,” Riley countered. “That is not to say we should ignore the fact that we have cops misbehaving. But it is to say to focus on that is to go wide of the mark. Cops are about six times as likely to be shot by someone black than the opposite. Yet we have [media] commentators selling this scenario that black men in America in poor communities walk around in fear of being shot by cops. That is not the case. They walk around in fear of being shot by other young black men. That is the reality. … The cops are in these neighborhoods because that is where the 9-1-1 calls originate.”

Is focusing on police brutality as the main problem going to reduce the black body count, Riley posited. No, he argued.

“If [police] are now overly concerned with being second-guessed of every decision they make, they are going to be more hesitant, they are going to be less aggressive when it comes to keeping peace in these neighborhoods. That will result, I fear, in a higher black body count.”

It was just one of many issues tackled by the two men during the one-hour debate Monday night at UCLA. They also disagreed on whether affirmative action has helped or hurt African-Americans, and if it’s American’s collective duty to provide “insurance” for victims of racism.

The two debaters’ speaking styles were polar opposites: Riley was soft-spoken, concise, and calm, whereas Professor Kennedy bellowed, used verbose rhetorical flourishes, and often displayed intense emotion.

In Riley’s opening statement, he stressed two major points. First, that liberal social policy since the Civil Rights Act of 1965 has been at best ineffective and at worst counterproductive toward black advancement. Second, that in order to advance, blacks must face tough and often taboo questions about cultural problems within black communities, and cease blaming their problems on residual white racism.

One overarching theme for Riley was the juxtaposition between equality of opportunity and equality of outcome. Riley stated the government should only be in the business of guaranteeing the former and should not be striving for the latter.

Kennedy structured his opening argument in favor of affirmative action, and the other liberal social policies that Riley called ineffective, by drawing a parallel between these programs and other types of “social insurance” the government provides.

Kennedy argued that Americans collectively provide insurance for disasters, disability, age, economic depression like that seen in the financial crisis of 2008, and the destruction wrought by the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He then offered the premise that racism is a social catastrophe that should be viewed by government in a similar fashion as the other sorts of catastrophes he mentioned. He stressed that it is American’s collective duty to provide “insurance” for victims of racism. Kennedy proclaimed one form this insurance could take would be to guarantee every person in the country a job, whether they have the skills for the job or not.

In the rebuttal period, Riley called Kennedy out for not addressing his claim that the last fifty years of liberal social policy have led to black retrogression. He said the argument against affirmative action and other similar policies is a pragmatic rather than a theoretical one.

Riley said there is 50 years of history showing that such policies simply don’t work. He gave some evidence to bolster his argument: between 1940 and 1960 the black poverty rate fell by 40 percent, all before the Civil Rights Act was passed, and the rate of decrease in the poverty rate has slowed since liberal policies began to be implemented in the 60s. He also noted that black unemployment rates and incarceration rates were lower in the 60s than they are now.

Riley conceded that the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were “liberalism at its best,” but that most of the economic gains blacks have made can’t be attributed to government policies such as affirmative action. Riley noted that the number of black “white-collar workers” quadrupled between 1940 and 1970, before affirmative action was implemented.

In Kennedy’s rebuttal, he refuted Riley’s argument that the blame for black retrogression should be laid at liberalism’s doorstep, noting liberals haven’t had a monopoly over policy in the last fifty years inasmuch as Reagan and both Bushes have served as presidents.

In addressing affirmative action, Kennedy flashed his oratory skills: “I am an unapologetic champion of affirmative action, I am an affirmative action baby, I’m not suffering a neurotic tremor about that.”

Responding to Riley’s point that pragmatism should be the focus in designing policy, Kennedy said “I’m experimental, even if it’s a conservative idea, give it a shot to see if it works.”

Roughly 75 people turned out for the debate. Matt Malkan, a professor of physics at UCLA who attended, said the debate was historic, with nothing like it happening in the last 10 to 15 years on campus.

It was hosted by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, an organization dedicated to “Educating for Liberty” and co-founded by conservative icon William F. Buckley.

College Fix reporter Josh Hedtke is a student at UCLA.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.