‘I’m doing this for the sake of the research’

Steven Jacobs has described some of his time in the academy as “agony.”

The University of Chicago PhD spent the last half-decade in a grueling fight to gather and publish research related to the American abortion debate. During that time he was ridiculed, mocked and defamed; accused of committing academic dishonesty, politicizing science and conducting his work with personal bias; compared to the Ku Klux Klan; and in general painted as an unprofessional radical who was, in one academic’s words, “not deserving of a PhD degree.”

All of this came about simply because Jacobs asked thousands of scientists several questions about when they believe human life begins – questions one respondent referred to as a “trap” and another called “horribly manipulative.”

The results of Jacobs’ work would eventually reveal a stunning fact about American academia in the field of biology: professors overwhelmingly agree with the pro-life position that human lives begin at conception. Gathering that data, arguing it, and getting it published, however, was a crushing and drawn-out affair.

The College Fix has been in contact with Jacobs since March. The scholar did not want to discuss his situation on the record with any media prior to arguing his dissertation for fear of professional consequences.

At one point, Jacobs said, an academic specifically instructed him not to speak with The Fix, citing several articles it has published about the abortion debate on college campuses. The professor was concerned that any reporting done by The Fix on Jacobs’ work “could be used by pro-life advocates.”

Jacobs requested that the professors involved in this saga be kept anonymous out of concern for professional repercussions.

A five-year ordeal

In lengthy documentation provided by Jacobs as well as a phone interview, the scholar details his path from grad student to abortion researcher. In graduate school at the University of Chicago, Jacobs said, he sought to write a paper about the American abortion debate for a qualitative research class. The professor of the class explicitly instructed him not to write about that debate.

“When I spoke with my peer mentor and other students in my program, I heard different voices saying the same thing – that I should not research the abortion debate,” he said, adding that “it was expressed to me that I should not do work on abortion because of who I was: a white, Christian man.”

Jacobs conceded, putting off his abortion research until 2014. In the meantime he attended law school, after which he returned to the University of Chicago. There, under the instruction of an advisor Jacobs described as a “fearless thinker,” he began developing a survey for academic biologists that would gauge their opinions on a critical facet of the abortion debate: when individual human lives begin.

That question is a central tenet of the abortion debate. Most pro-lifers insist that human lives begin at conception, and pro-choicers generally insist otherwise, claiming either that human lives begin at birth, that the answer is unknowable, or that the question is ultimately irrelevant.

To bolster his thesis, Jacobs actually conducted “pilot work” on this question. He surveyed 2,899 American adults, finding that a large majority of respondents believe that the question “When does a human’s life begin?” is important to the abortion debate. The poll also revealed that a large majority of respondents, including a larger share of pro-choice individuals, “selected biologists as the group most qualified to determine when a human’s life begins.”

Jacobs began surveying biologists at American institutions, but “within days” of beginning his research, the trouble began.

Asking biologists basic questions on human development

The survey questions were directed specifically at determining respondents’ beliefs about when individual lives begin. Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with two “implicit statements.”

The first read: “The end product of mammalian fertilization is a fertilized egg (‘zygote’), a new mammalian organism in the first stage of its species’ life cycle with its species’ genome.” The second declared: “The development of a mammal begins with fertilization, a process by which the spermatozoon from the male and the oocyte from the female unite to give rise to a new organism, the zygote.”

A subsequent “explicit statement” asked recipients to respond to this premise: “In developmental biology, fertilization marks the beginning of a human’s life since that process produces an organism with a human genome that has begun to develop in the first stage of the human life cycle.”

An open-ended essay question asked respondents to answer “from a biological perspective” the question “When does a human’s life begin?’”

The questions are firmly couched in the premises and presumptions of biological science rather than any political ideology. And yet the backlash to the survey was relentless and viciously negative.

One respondent to Jacobs’ survey “accused me of nefarious intentions and threatened to sabotage my work by telling other biologists to not participate in my study,” the scholar said. That professor “ultimately reported me to my school’s ethics committee.” Jacobs’ advisor told him to halt his data-gathering, though eventually that advisor would defend Jacobs before the school’s ethics committee, after which the research was allowed to continue.

Further troubles

However, after beginning the survey again, this time in September 2016, “my study was once again canceled within a week.” Jacobs’ advisor was beleaguered with accusations that he himself “had no integrity for even approving [the] research.”

“I was told that my survey seemed like it was developed by the Ku Klux Klan; I was told that my work could expedite the extinction of the human race; I was told that I should be ashamed of myself since I was damaging the reputation of the University of Chicago,” Jacobs said.

He provided The Fix with a staggering number of responses from the survey respondents. Those emails range from the affirmative to the immaterial to the aggressively vituperative.

“A VERY poorly designed questionnaire. I doubt that ANY serious conclusions can be drawn from it,” one response reads. “Abortion has been legal for over 40 years. It’s time for all the religious nuts to get over it,” said another. “Abortion is a woman’s right; the state has no role in the decision to abort whatever the reason (medical, cultural, economic),” a third reads.

“Abortion is not about biology. Please don’t use this survey to say ‘Look, even biologists are pro-life’ because that is absolutely not what my answers mean,” another respondent said.

Others equivocated on the relevance of the questions. “Biology deals with facts. When a life, with value, begins or ends is best decided by philosophers and ethicists,” said a respondent.

Another wrote: “As a scientist, I agree that life begins at fertilization. But, as a citizen of this democracy, I support a woman’s right to choose. From that perspective, I adopt the opinion that life begins at first heartbeat.”

Another criticized Jacobs for referring to the two sides of the abortion debate as “choice” and “pro-life.” That professor requested that the terms be classified as “choice” and “anti-choice.”

“This is some stupid right to life thing…YUCK I believe in RIGHT TO CHOICE!!!!!!!” another professor wrote.

Jacobs told The Fix that he believes the overwhelmingly negative response to his research has damaged his standing in academia, perhaps irreparably.

“I have gotten the sense that this has been talked about a lot,” he said. “I’ve been regularly told I can’t get a job in academia. I’ve been told don’t try. I’ve been told maybe a Christian school would hire me. “

Except for “one email I sent out to one lab about a research assistantship, I haven’t even looked into academia,” Jacobs continued. “I knew what was going to happen before it happened. I told myself I was going to do this for the sake of the research, not for the sake of my career.”

Advisor flip-flops on support

Due to the ongoing negative reactions to his queries, Jacobs was told to hold off on any further data research until he had defended his dissertation proposal before a committee. After a year of preparation, he successfully did so. But when he approached his advisor to restart the study, he was shocked to find that the supervisor had changed his mind about the undertaking.

“He began to suggest that my research was unethical, as I was ‘leading them down a primrose path’ and tricking biologists. I was dumbfounded, as we had worked on the study and developed the methodology together,” Jacobs said. In the end, that did not matter:

[The advisor] said that he would step down as my advisor if I continued the research and, if he stayed on my committee, he would be unlikely to approve my dissertation. To say I was devastated would be an understatement. I was on my way to borrowing a quarter-of-a-million dollars to finance my education; I had turned my back on opportunities to make a ton of money as a corporate attorney; I had refused to sit for the bar so I would not be tempted by a legal career when things got tough; I had endured insults about my religion, accusations about my motivations, and attacks on my personal and professional integrity — all so I could do this work.

That advisor would eventually step down from supervising Jacobs’ work. The Fix reached out to the advisor for comment via email Tuesday morning; Jacobs did not give The Fix his name until Sunday. He did not immediately respond. Another advisor has not responded to a Tuesday morning request for comment.

Eventually, after numerous rejections, Jacobs found a professor willing to serve as a principal investigator over his research. He continued to face relentless pushback from his academic community. At one point there was concern that the ethics committee “would not only stop my data collection, once and for all, but that they could invalidate all of the data I had collected,” rendering it useless for study.

Over the next year, while preparing his thesis, Jacobs continued to receive criticism from his former advisor, who claimed that the premise of the research was a “red herring.”

“In the days leading up to my defense, he made me remove any mention of that study from my dissertation’s abstract, accused me of sounding like a pro-life pundit, and said that he didn’t want to have his name on a document that could be cited by pro-life people,” Jacobs said.

At Jacobs’ dissertation defense, that advisor pushed back against Jacobs’ thesis, stating that he was “worried that pro-life people would use my work” and that “it would be a poor representation of the University of Chicago, if that were to happen.” Jacobs said he observed “surprised expressions” among the dissertation committee regarding the advisor’s aggressive objections. After the argument was over Jacobs said he received “comments suggesting that I must have a high pain threshold” and commendations for withstanding the advisor’s “onslaught of attacks.”

Eventually, the dissertation was approved, and Jacobs was awarded a Ph.D. In spite of his tribulations during his research, Jacobs expressed gratitude for both his university and his peers there.

“Ultimately, I think the University of Chicago should receive credit for not dismissing me as a student, for eventually approving my research, and for allowing me to graduate after writing a dissertation about fetal rights. It is possible that I wouldn’t have been able to do this at another institution, so I am grateful to everyone involved,” he said.

Data reveal stunning majority support of pro-life position

Negative reactions to his survey aside, Jacobs’ research revealed that, whatever their politics, large majorities of biology professors support the pro-life contention that human lives begin at the moment of fertilization.

Of the two “implicit questions” posed by Jacobs, which asked biologists to respond to the contention that the development of a mammalian organism begins at the moment of fertilization, around 90 percent of respondents answered in the affirmative. To the question that “fertilization marks the beginning of a human’s life,” fully three-quarters of respondents said yes.

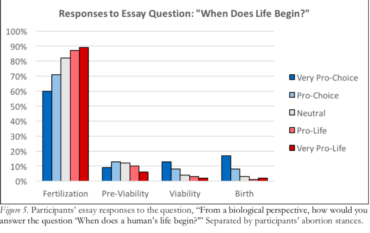

Responses to the essay question “When Does Life Begin?” were also lopsided in favor of the pro-life position. While nearly 90 percent of “very pro-life” respondents answered that it begins at fertilization, still nearly three-quarters of “pro-choice” respondents answered the same. Around three-fifths of “very pro-choice” respondents felt the same.

Responses to the essay question “When Does Life Begin?” were also lopsided in favor of the pro-life position. While nearly 90 percent of “very pro-life” respondents answered that it begins at fertilization, still nearly three-quarters of “pro-choice” respondents answered the same. Around three-fifths of “very pro-choice” respondents felt the same.

These responses shed valuable light on a contentious and critical question of the abortion debate. Pro-choice pundits and advocates have for years argued that the question is in effect an unknowable one. Former Planned Parenthood CEO Cecile Richards, for instance, said several years ago that, according to OB-GYNs with whom she had spoken, “there is no specific moment when life begins.” An article at Wired from several years ago also declared that “science can’t say when a baby’s life begins.”

Jacobs’ large-scale survey, apparently the first of its kind, may finally put to rest the notion that the precise moment at which human life begins is unknowable. That is his hope, in any case. Jacobs expressed a desire that the abortion debate move away from “When does life begin?” and toward “Is it okay to kill unborn humans?”

“A human’s life begins at fertilization. An abortion is the intentional killing of a human, and thus should be recognized as a homicide,” Jacobs told The Fix over the phone. He noted that he does not use the term “murder,” as that has both legal and negative connotations. Rather, he uses the word “homicide,” and says that the central question about abortion is: “When is that homicide justifiable?”

Jacobs said the abortion debate should be reframed around a question of rights, a discussion he hopes his research will help clarify and move forward.

“Let’s stop debating whether a fetus is a human and start debating whether all humans have rights and, if so, how to balance one human’s right to abort and another human’s right to life,” he said.

MORE: Over a dozen biology professors won’t say when human life begins

IMAGE: Tipping Point With Liz Wheeler on OAN/YouTube

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.