ANALYSIS

When a Rutgers University journalism professor’s infamous tweet went viral earlier this month, claiming that America was more “brutal” than the self-proclaimed Islamic State because of the death toll from modern American military campaigns, the response was predictable.

The debate on Fox News and other outlets focused on the inflammatory comparison and whether Deepa Kumar was a hypocrite for trying to stop Condoleeza Rice’s commencement speech at Rutgers. (Rice eventually withdrew herself following a disinvitation campaign by Kumar and her colleagues.)

What interests me more as an Iraq war veteran is that no one seems to be challenging the supposed facts that Kumar quoted in her tweet.

Kumar cites the far-left website Democracy Now! for the 1.3 million-killed claim, and that site in turn cites a study that attempts to quantify how many casualties have occurred since the U.S. military interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Yes ISIS is brutal, but US is more so, 1.3 million killed in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan #NoToWar @democracynow http://t.co/fjaszeKTYD

— Deepa Kumar (@ProfessorKumar) March 26, 2015

There are a few problems with the study, conducted by the German affiliate of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War.

Statistical sloppiness

First, it’s a thinly-veiled progressive opinion piece masquerading as a scientific study, a problem that plagues academia and undermines the credibility of academics. At every turn and corner, the authors make opinion-based judgments about the wars rather than aiming for objectivity.

Second, the study provides several measures to quantify the number of deaths, the highest estimate (100,000 to 1 million) coming from Iraq.

It is telling that Kumar cited the upper end of this scale, while the Iraq Body Count project – which records “actual, documented deaths” from the media, morgue and other hard records – gives a range of about 142,000 to 161,000 “documented civilian deaths from violence.”

Studies that claim higher numbers used questionable statistical methods, which even Kumar’s own source notes (page 16). Baghdad and other conflict cities had a much higher casualty rate than the rest of Iraq, meaning that if they were oversampled, the figures would skyrocket. Resident surveys are also notoriously unreliable in Iraq because families may not want to disclose that a son is fighting in the insurgency or that they are hiding a family member facing numerous death threats – and report both as dead.

Further, any serious scholar of the Iraq War knows that counting casualties is an inexact science. After a suicide vest is detonated in a busy market, the local hospital has the grisly task of putting together victims torn apart by the blast.

Frequently, there are body parts left over from victims that were mostly vaporized due to their proximity to the explosion. When the hospital staff is asked for a casualty count by the government and media, it is really an educated guess based on the number of intact corpses and leftover body parts.

Speaking from personal experience during my service in Iraq, I can say in full confidence that Kumar’s upper-boundary figure is not close to credible. It would mean 274 people were dying on average each day over 10 years, which is one to two mass-casualty events per day – something that wasn’t happening even at the height of the war.

This eagerness to peddle figures that aren’t anywhere near verifiable, and with such certitude, is disturbing for a professor of journalism like Kumar, who should be promoting ethical media practices rather than flights of statistical fancy.

Treating terrorists like children

Kumar also conflates the intentional targeting of civilians with casualties that occur due to mistakes or collateral damage.

Of Iraq Body Count’s mid-100,000s range of deaths, the vast majority likely consists of incidents such as a suicide vest detonation in a crowded market, car bomb in a residential neighborhood, or illegal checkpoint in which militants pulled civilians out of their cars and executed them for following the wrong sect of Islam.

Those who opposed the Iraq War claim that removing Saddam Hussein created a power vacuum that was filled with extremists.

Yet these adults made the conscious decision to wear explosives, walk into crowded markets and blow themselves up: How is the U.S. responsible for that? Why aren’t the leaders and perpetrators of these horrific attacks assigned most of the blame?

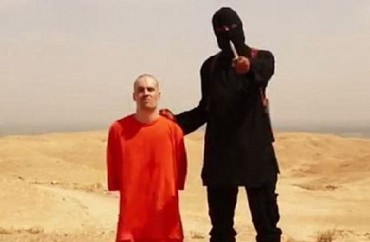

Comments like Kumar’s are based on the assumption that perpetrators of horrific violence are to be considered children who are not responsible for their actions, despite the fact that many terrorists, such as the “notorious” ISIS executioner Jihadi John of London, are highly educated.

There is no question that the U.S. military’s mistakes led to civilian deaths, but that number is a tiny fraction of the total casualty count.

It’s undisputed that the U.S. military follows established rules of engagement designed to minimize casualties, in contrast to an organization that is inventing new horrific ways to kill civilians in order to generate splashy media headlines.

Let’s start a dialogue

I’m baffled by Kumar making such a statement in her tweet, based on extremely sketchy evidence. Is it a product of being trapped in an echo chamber in academia? Is it an attempt to gain notoriety and credibility in far-left circles?

As a professor of journalism, Kumar’s willingness to grasp at paper-thin evidence that justifies her radical beliefs raises serious questions about her professionalism and competence. Student journalists under her tutelage should be concerned about the quality of instruction they are paying for.

Kumar told Inside Higher Ed following the outcry about her tweet that “she welcomes debate and engagement on the issues raised in her original post.” That’s why I’ve reached out to Kumar in good faith, asking her to explain her claims and thinking. To start a real dialogue, not just a tweetstorm.

The ball is in your court, professor.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.