ANALYSIS: Scholar makes strong argument to defend, revive traditional higher education: ‘The liberal arts became not just for free men, but the arts capable of making men free’

In the course of current battles over higher education, the liberal arts have become a prime target for attacks from the right, the left, and the apolitical.

From the right, liberal arts colleges are seen as prime breeding grounds for wokeness and rife with left-wing professors bent on the indoctrination of their students.

From the left, a traditional approach to liberal arts has been portrayed as a Trojan horse for systemic racial discrimination, with some liberal commentators opining on how the Western canon has “fascistic appeal to the far-right desktop warriors defending white civilization from the global majority.”

On the practical, less-political side, liberal arts are often conceived as useless, damning those who receive them to a future of low-paying service jobs and years of academy training wasted.

Given this bevy of attacks, how can conservatives approach the liberal arts, and is the pursuit even worth the time?

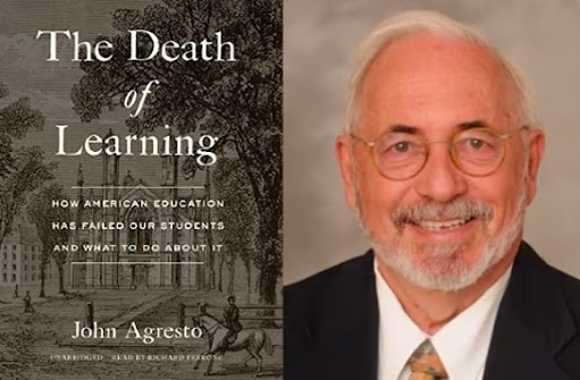

John Agresto certainly thinks so. A higher education expert and former president of St. John’s College in New Mexico, Agresto sat down with AEI Fellow Benjamin Storey on Jan. 23 to explain the conservative case for the liberal arts, an argument he made against the backdrop of his latest book, “The Death of Learning: How American Education Has Failed Our Students and What to Do About It.”

The situation, Agresto argues, is a dire one.

“The liberal arts are dying. They are dying because most Americans don’t see the point of them,” his book’s description reads. “Americans don’t understand why anyone would study literature or history or the classics … when they can get an engineering or business degree. … In this atmosphere, it’s hard to convince parents or their progeny that a liberal education is all that wonderful.”

In his conversation with Storey, Agresto explained the liberal arts are historically rooted in the desire to liberate the mind into the skills of critical thinking and the ability to ask big questions.

“The liberal arts became not just for free men, but the arts capable of making men free,” Agrestosaid. “You could be free of the cave of opinion that you lived in.”

On a political note, Agresto fields the question: why liberal arts?

“Quite paradoxically, they [liberal arts] are the conserving arts,” he said, noting how many of America’s founders, including James Madison, John Adams and George Washington, were trained in the liberal arts—it was that liberal arts training that led them to the development of America’s conservative founding philosophy.

“This is where culture, tradition, great books find their home,” he said.

Yet that home is in danger, and Agresto freely admitted how the critiques of liberal arts come from both sides of the political aisle: “The left finds them … very reactionary, very conservative, and the right thinks of it as nothing more than a bunch of woke activists.”

Yet, he added, the ability to think critically and ask big questions are crucial for anyone seeking to preserve Western civilization; indeed, to understand the West at all.

To Agresto, some of the strongest blame falls on professorial shoulders: “We have failed as liberal arts professors to show how the liberal arts are personally useful.”

Even speaking as a liberal arts educator, Agresto reminded his audience that he doesn’t begrudge or dismiss non-liberal-arts subjects or believe them to be inferior career paths.

“I really have great respect for the technical and vocational and professional arts. They really are, you can call them servile, but some of them are very high arts,” he said. “To be a doctor, to be an engineer, to be an architect, you have to know not only things that are wonderful to know, but you have to know things that people need.”

Aside from his view of the modern university as needing both liberal and vocational arts, Agresto’s optimism extends into the future of the liberal arts. To him, his newest book shouldn’t be read as overly negative, despite the title.

“It’s not an obituary. There are lots of things going on that are hopeful,” he said, pointing out liberal arts programs at places like Thomas Aquinas College in California, St. John’s College in Maryland, and Princeton’s James Madison Program.

In Agresto’s words, the fate of American liberal arts lies in the ability to appeal to Americans’ love for the practical.

“Americans don’t dislike the beautiful,” he says. “They just want the beautiful to be useful.”

MORE: ‘Wonderful treasures’: Former college president writes passionate defense of liberal arts

IMAGE: Serato / Shutterstock

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.