Twitter can be a rough place for a scholar

On May 17, English professor Christopher Schaberg wrote an article about why he quit Twitter. However, Schaberg also wrote an Inside Higher Ed piece in 2016 called “The Academic Advantages of Twitter,” a position which he says he still endorses.

By synthesizing Schaberg’s advice, past and present, academics as well as the rest of us can learn to use Twitter prudently and effectively.

The alternatives are not pretty. As Schaberg notes, as many have done before him, Twitter is a black hole of distraction, pettiness and negative emotion. It also creates a permanent record that anyone can exploit, to cancel you or worse.

This may be in part because the medium of communication to which Twitter habituates us – 280-character bits of text – doesn’t allow for much depth, focus or nuance. Journalist Johann Hari makes this point in his new book, “Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention – And How to Think Deeply Again:”

If your response to an idea is immediate, unless you have built up years of expertise on the broader topic, it’s most likely going to be shallow and uninteresting.

Whether people immediately agree with you is no marker of whether what you are saying is true or right—you have to think for yourself. Reality can only be understood sensibly by adopting the opposite messages to Twitter.

The world is complex and requires steady focus to be understood; it needs to be thought about and comprehended slowly; and most important truths will be unpopular when they are first articulated.

Hari also said that Twitter has made him into a shallower, more vicious version of himself.

“I realized that the times in my own life when I’ve been most successful on Twitter—in terms of followers and retweets—are the times when I have been least useful as a human being: when I’ve been attention-deprived, simplistic, vituperative,” he stated.

Schaberg might agree, writing that the distraction from Twitter “might be more cumulative and exponentially impactful than you realize.” He wrote that it easily prompts ugly mental states such as irritation and jealousy.

“It’s just so easy to see someone else’s accomplishment, book contract, award or fellowship announcement and feel somewhat sad inside—and, in fact, jealous,” he wrote.

“And that can be the case even when you’re simultaneously happy for them!”

Perhaps because the medium encourages shallow reading and vices of character, your tweets are likely to be misinterpreted – and those misinterpretations can have fatal consequences.

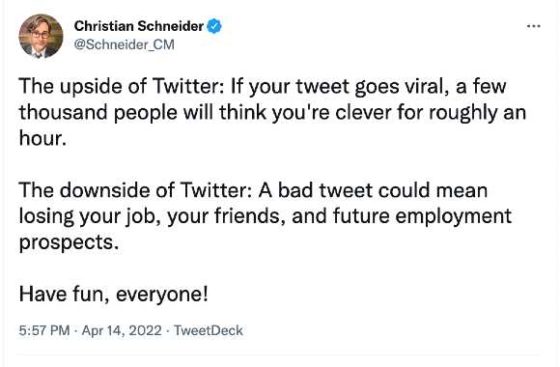

As my colleague Christian Schneider said on Twitter, the site’s upside is that you can say things that make people think you’re clever. Its downside is that a bad tweet can cost you pretty much everything.

Virtually every media outlet – very much including this one – has documented the sad sagas of respected, successful professionals who have had their careers and reputations ruined by a thoughtless or tone-deaf tweet.

Professor Ilya Shapiro, top Columbia doctor Jeffrey Lieberman, journalists Nir Rosen and Justine Sacco: these folks and many others would be happily out of the headlines and busy with the interesting and important jobs they lost if they had just stayed quiet on Twitter.

Perhaps sometimes they deserve it; in most cases they do not.

But while you can’t control how other people react to what you say, you can control what you write on the internet. Tweet with care, lest your own words be your undoing.

Twitter is a way to ‘dare to be public’

However, as Schaberg-in-2016 correctly noted, Twitter can be a powerful tool for good and career advancement, if you use it well.

Twitter can be a way to test your writing ideas, and “make your prose stronger, clearer, and most important, shorter,” Schaberg wrote.

Just maybe don’t make your prose too controversial.

Twitter can also be a way to share work that otherwise might never see the light of day. That’s why it’s an excellent tool for self-promotion, as Schaberg correctly stated. People might not have time to read academic articles or books, but they have time to scroll through your tweets.

Writers and others who need to publicize their work can do it on Twitter quickly and effectively.

“When I talk to editors about this issue…they invariably tell me they prefer it if their authors are active on Twitter,” Schaberg wrote. “It is not only aiding the struggling and overwhelmed marketing efforts of publishers but it is also a way to do your work justice, to dare to be public about your intellectual work.”

Academics and journalists can even reference tweets as source material for articles and books.

Though the medium is limited, Twitter also somehow manages to house sharp and “lively critique,” Schaberg wrote. “It is a vibrant medium for pithy reviews, trenchant commentary, and subtle demystification.”

The key thing to note here though, I think, is that the people who are most interesting on Twitter are simultaneously the most interesting off of Twitter.

I value Twitter, as do most of my colleagues and friends. But it’s no substitute for conversations, reporting, deep reading, and careful writing. We only get glimpses of that on the platform.

So no matter what you do for work, follow Schaberg’s advice, past and present: Tweet productively and responsibly, and don’t let it overwhelm or destroy the rest of your life. A 280-character message is too short to argue a point worth making, to or chronicle a life well lived. You need to have some substance to condense it down to size.

MORE: Independent-minded scholar provides linguistic sanity

IMAGE: Christian Schneider/Twitter