Not many students in America today are taught that blacks owned slaves in America pre-Civil War.

But it’s an interesting and relevant fact, especially as a tool to help debunk the flawed New York Times’ “1619 Project” curriculum used in many schools today.

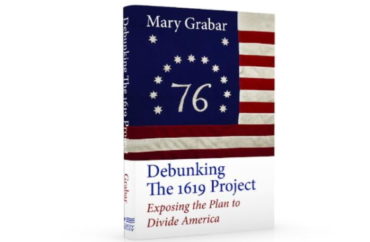

“Debunking The 1619 Project,” a new book published Tuesday and authored by scholar Mary Grabar, is billed by its publisher Regnery as a detailed and extensive take down of the “divisive and false” narrative of the project and its corresponding curriculum.

The book includes chapters on topics such as Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln. The 1619 Project had argued the American Revolution was fought to maintain slavery and Lincoln was actually a racist.

Other chapters take more philosophical tactics, such as Chapter 11, “Choosing Resentment — or Freedom?”

One of the main tenets of the 1619 Project is the argument that all of America was built on the back of slavery. Grabar’s Chapter 7 takes on “A Not So Simple Story,” which details black U.S. slave owners pre-Civil War. The chapter is republished in full below with permission.

“Debunking the 1619 Project: Exposing the Plan to Divide America”

Chapter 7: “A Not So Simple Story”

There is a great deal of evidence, both anecdotal and official, that a significant number of African Americans acquired slaves when given the opportunity to do so. In recent years scholarly research on this issue has confirmed anecdotal evidence from stories, legends, and interviews.

Presbyterian minister and writer Calvin Dill Wilson, who in 1905 and 1912 attempted to gather such information for the North American Review and Popular Science Monthly, would no doubt have been glad to know that scholars would be going to county courthouses and reviewing records. One senses his frustration in the article he published in 1905 reporting that he had “asked dozens of Southern people, of advanced years, about negroes owning slaves,” only to have been told “that they ‘never heard of such a thing.’” Wilson acknowledged the difficulty of even asking such questions: “Psychologically, after all we have read and heard of the pathos and tragedy of negro slavery, it is of strange interest and unaccountable inconsistency that the negroes themselves should at times have had no apparent compunction in regard to buying their fellows at the block….”

The one book to which he was directed by the Library of Congress “barely glance[d] at the subject.” Booker T. Washington told Wilson that he had no “personal recollections” of such slave owners. Historians and attorneys in Louisiana, where the French and Spanish traditions of interracial marriage prevailed, could offer only recollections and no documentation. But in Maryland, he learned that “pure blacks, who had themselves been slaves and had been manumitted were frequently slave-owners.” One county court record he found revealed that “Draper Thompson, free negro…in 1824 bought and sold a negro man at public auction out of an estate for three hundred dollars.” And an “aged man, William W. Davis, eighty-eight years of age,” told Wilson that “he knew Thompson well in his own boyhood, that at one time he lived on a large farm, the Cremona Tract; he did not allow his slaves to associate with his own family, but made them eat and sleep in a separate house,” and when entering his home each of his slaves had “to doff his hat and carry it under his arm while doing so.”

Wilson also related other stories, including from a “Philip Roberts, a respectable colored man of Glendale, Ohio, who was a slave in Kentucky” and who told him “that he knew ‘Old Free Isaac,’ in Trimble County, Kentucky, who owned several negroes.” He said that “this same negro sold his own son and daughter South, one for $1,000, the other for $1,200.” And, Wilson reported, “Mr. Stevenson Archer, of Mississippi, states that he knew a pure-blooded negro, born free, by name Nori…who had before the Civil War, a large plantation in Mississippi, and owned about a hundred negroes. He was exacting, but not cruel, and he took excellent care of his slaves.” Wilson also recounted cases where slaves were purchased by family members to protect them.

Wilson also related other stories, including from a “Philip Roberts, a respectable colored man of Glendale, Ohio, who was a slave in Kentucky” and who told him “that he knew ‘Old Free Isaac,’ in Trimble County, Kentucky, who owned several negroes.” He said that “this same negro sold his own son and daughter South, one for $1,000, the other for $1,200.” And, Wilson reported, “Mr. Stevenson Archer, of Mississippi, states that he knew a pure-blooded negro, born free, by name Nori…who had before the Civil War, a large plantation in Mississippi, and owned about a hundred negroes. He was exacting, but not cruel, and he took excellent care of his slaves.” Wilson also recounted cases where slaves were purchased by family members to protect them.

Wilson continued his research after the publication of his original article. In 1907, he wrote to W. E. B. Du Bois, who was then teaching at Atlanta University, but Du Bois answered that he did not know where he would be able to “find much authentic data.” Most black slave owners, he guessed, were probably “mulattoes of the extreme Southern gulf states.” Du Bois suggested Wilson contact local historians there, as well as Colyer Merriweather of the Southern History Association and “a Mr. A. H. Stone,” both of Washington. Du Bois asked that Wilson share whatever information he found, for he was “curious…to know how much fact is behind the general statement.”

“Practically a Lost Chapter”

In a 1912 article, Wilson bemoaned the fact that the issue had “become for our generation practically a lost chapter,” with the full data never having been and probably never to be collected, given that much of the pertinent material had probably “perished through the burning of court houses, state houses and similar depositories of documents.” But at the Connecticut Historical Society, Wilson had found “a bill of sale from Samuel Stanton…dated October 6, 1783, to Prince, a free negro, of a slave woman named Binar.” And in the deed books of St. Augustine, Florida, he had found a record naming “Joseph Sanchez, a colored carpenter, who sold to Francisco P. Sachez a negro slave for three hundred dollars.” Also, “[i]n 1724, a servant named Margaret was sold to Scipio, ‘free negro man and laborer of Boston.’” And the “early records of Mobile, Ala.” showed that “Juan Batista Lusser, in 1797, was one of these negro slave-holders, as were also Julia Vilard, Simon Andry and the house of Forbes.” Wilson lists accounts of free blacks owning family members, including one in which a son sold his father after an argument. “Mr. George W. Brooks, of Atlanta,” recalled a colony “of free negroes, many of them named Epps,” in Person County, North Carolina, thought “to be descendants of the slaves set free by Mr. Epps, the brother-in-law of Thomas Jefferson.” Brooks recalled hearing a “free negro named Billy Mitchell” telling about his courtship of his future wife, whose father owned slaves, one of whom was so light-skinned as to appear white. Billy Mitchell then became a slave owner himself.

More examples included John Carruthers Stanly, born in Craven County, North Carolina, in 1722 of a white father and a mother from Africa. He married a black woman, became a successful barber, and owned sixty-four slaves and two large plantations. A “colored brick mason in New Bern,” a “dark mulatto” named Doncan Montford, owned slaves, one of whom, Isaac Rue, also a mason, he sold to a lawyer named George S. Altmore. Rue married a free black woman. Their children were free under North Carolina law. “One of their grandsons, Edward Richardson, was at one time postmaster of New Bern, appointed to the office by a Republican president.” There was the case of Dilsey Pope in Columbus, Georgia, who sold her husband to a white man in anger, and then to her regret could not get him back.

Wilson reported that a 1790 census listed 48 free “negro slaveholders” owning 143 slaves. “The ‘List of the Taxpayers of the City of Charleston, S.C., 1860,’ names one hundred and thirty-two colored people who paid taxes on three hundred and ninety slaves in Charleston.” From among the “large number of individual instances of slaveholders in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, Maryland, both the Carolinas, Missouri, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, the District of Columbia, Delaware, Mississippi, and Louisiana,” Wilson named a few, including “Thomas Blackwell, who lived in Vance County, N.C.,” and “owned a favorite negro name Tom…a fine blacksmith,” who “around 1820” was allowed to “buy his freedom at a price far below his worth. … Tom prospered and bought two or three slaves”; William Chavers, “a well-educated negro who bought a good deal of land in Vance County, from 1750 to 1780” and “owned a good many slaves”; and Chavers’s descendants, who “for several generations were slaveholders.”

Quoting observations by Frederick Law Olmsted in “The Cotton Kingdom” and “A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States,” Wilson concluded his 1912 article by noting how little additional information he had been able to acquire since 1905 in spite of inquiries to “state librarians, public librarians, historians, historical societies and a host of individuals.” There was “no treatise specifically on the theme” of his research, not even an encyclopedia article, but “only scattered references…in a few books and in files of newspapers. The bulk of the facts is still buried in unpublished documents in court houses, historical societies and libraries. There are probably a few hundreds of people still living who have recollections of this phase of slavery. So we are justified in calling this subject, in its completeness, a lost chapter.”

Though many of these records, like other records of African Americans, have been lost, many have been found since Calvin Wilson wrote his article. But the issue has been discussed very little—as Wilson guessed, for “psychological” reasons. And also for political reasons. Attention on black slave owners would complicate the kind of narrative that The 1619 Project advances, which presents blacks and whites as monolithic groups of victims and exploiters, respectively. One rarely, if ever, finds mention of black slave owners in textbooks and curricula. A teacher who even knows about this aspect of slavery will be instructed to “downplay” it in the classroom—something I observed firsthand during the question-and-answer session of a panel discussion at the 2014 meeting of the Organization of American Historians. The panel, “Boundaries of Freedom: Teaching the Construction of Race and Slavery in the AP U.S. History Course,” was put on by the College Board, which writes the Advanced Placement exams and guidelines, and included a presentation by UC Irvine professor Jessica Millward on using playacting in class, such as of a slave owner whipping a six-months-pregnant slave while she lies facedown, her belly in a hole to protect the future “property.”

The dramatization of the history of blacks who owned slaves, in contrast, seems to cause discomfort, as is evidenced by Janet Maslin’s review of Edward P. Jones’s Pulitzer Prize–winning historical novel The Known World for the New York Times. The book is historically accurate, but Maslin downplays “the unusual setting” of “the unsettling, contradiction-prone world of a Virginia slaveholder who happens to be black.” And while she admits “[s]uch situations did exist,” she also takes care to say that “Mr. Jones teases his reader by occasionally citing some nonexistent scholarly treatise on the subject.”

The fact is that scholarly treatises on this subject do exist. Carter Woodson’s 1922 The Negro in Our History examined the class distinctions among “free Negroes,” with “social lines” as “strongly drawn as between the whites and the blacks.” Many of the “well-to-do free Negroes…owned slaves, who cultivated their large estates. Of 360 persons of color in Charleston, 130 of them were, in 1860, assessed with taxes on 390 slaves. In some of these cases, as in that of Marie Louise Bitard, a free woman of color in New Orleans, in 1832, these slaves were purchased for personal reasons or benevolent purposes…. They were sometimes sold by sympathetic white persons to Negroes for a nominal sum on the condition that they be kindly treated.” Wealthy free blacks able to own plantations with slaves were exceptions among the “well-to-do” persons of color, who were usually in the artisan class in southern cities. Woodson did find several striking examples, though: “Thomy Lafon of New Orleans,” who owned half a million dollars in real estate; in 1833 Solomon Humphries, owner of a successful grocery store in Macon, Georgia, “accumulated about twenty thousand dollars worth of property, including a number of slaves”; “Cyprian Ricard bought an estate in Iberville Parish, with ninety-one slaves, for about $225,000”; in Natchitoches Parish, Marie Metoyer “possessed fifty slaves and an estate of more than 2,000 acres,” and Charles Rogues “left in 1848 forty-seven slaves”; Martin Donato of St. Landry, who upon his death in 1848 left “a Negro wife and children possessed of 4,500 arpents of land, eighty-nine slaves and personal property worth $46,000.”

Woodson expanded on this research in Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States in 1830, published in 1924. John Hope Franklin devoted part of a 1943 monograph to the subject. And in the twenty-first century, Paul Heinegg, an engineer by training, published his research about his wife’s ancestors from North Carolina, who had “descended from a community of African Americans who had been in Virginia since the colonial period,” as a biographical note states. He extended his research to that of other families in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, and Delaware, and found white acceptance of blacks and ownership of black slaves by black free persons to be more widespread than one would think.

Changing Laws and Conditions

Although a 1670 act in the Virginia House of Burgesses stipulated that “all servants not being Christian imported into this colony by shipping shall be slaves for their lives,” and another Virginia law, in 1682, denied freedom to imported “Negroes, Moors, Mullatos or Indians,” the line “between freedom and slavery was extraordinarily permeable,” as the historian Ira Berlin remarks in the foreword to Paul Heinegg’s genealogical study, and “[v]arious peoples of European, African, and Native American descent crossed it freely and often. In such socially ill-defined circumstances, white men and women held black and Indian slaves and white servants, and black men and women did like. Peoples of European, African and Native American descent—both free and unfree—worked, played, and even married openly in a manner that would later be condemned by custom and prohibited by law…. Everywhere whites, blacks, and Indians united in both long term and casual sexual relations, some coerced and some freely entered.” Such racial intermingling had long been known in the black community and had been discussed frequently by African American journalist George S. Schuyler (1895–1977) in the Pittsburgh Courier.

The very existence of the laws against “miscegenation” serves as proof of the frequency of sexual relationships that crossed the race barrier. Schuyler, who was married to a white woman, routinely attacked the hypocrisy of such laws and commented on the famous Rhinelander case in the 1920s, when Leonard Rhinelander sued (unsuccessfully) for an annulment of his marriage to Alice Jones Rhinelander because she had not disclosed her mixed racial heritage. But Schuyler did not have the luxury of investigating genealogical records. Heinegg, who did, found that “most free people of color had their beginnings in relations between white women (servant and free) and black men (slave, servant, and free). The mixed-race children of servant and slave women and white men of property made up a scant 1 percent of the free children of color” in the colonial period. The relationships in the other 99 percent often represented “long-term and loving commitments.”

Heinegg documents the “legal proscriptions on sexual relations between white and black, particularly between white women and black men” that became harsher over time. Mixed-race children became illegitimate by definition. They could be bound out to servitude for upwards of thirty years, and their mothers, if servants, received additional terms of servitude. The legal rights of free blacks became increasingly circumscribed, as “they were barred from voting, sitting on juries, serving in the militia, carrying guns, owning dogs, or testifying against whites.” These gradually tightening restraints on African Americans contradict the “slavocracy” origin thesis of The 1619 Project.

And yet, there were exceptions, in contrast to the black-white picture painted in The 1619 Project. Despite their increasing legal disabilities, by the mid-eighteenth century “a small cadre” of prosperous, “property-owning free people of color had emerged in the Southern colonies. Even as slaveholders tightened the noose of proscription and exclusion, these landed, prosperous free men and women made their presence felt,” appearing in court to protect “themselves and their property” and seeking “out churches to register their marriages and baptize their children.” Sometimes they assisted “their less fortunate brethren, helping to protect them from unscrupulous men and women who sought to transform free people of color into slaves, either through legal chicanery, illegal subterfuge, or outright force.”

Heinegg says, “Many free African American families that were free in colonial North Carolina and Virginia were landowners who were generally accepted by their white neighbors”; most of these families had originated in Virginia, where they became free in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Especially welcomed by whites were blacks moving to frontier areas in North Carolina. They were not seen as a threat because the overall percentage of slaves was low, and because “several of these African American families owned slaves of their own.” The fact that they owned land also made them more acceptable. Mulattoes had a special status. In the Caribbean they enjoyed a higher status than those of pure African descent. In mid-eighteenth-century North Carolina, mixed-race families were counted in some years by state tax assessors as “mulatto” and in other years as white.

Slavery was being codified on the basis of race, with laws making it more difficult for blacks to purchase slaves for commercial purposes, as Russell explained in the Journal of Negro History, but Heinegg found exceptions:

“On 9 November 1762 many of the leading residents of Halifax County petitioned the Assembly to repeal the discriminatory tax against free African Americans, and in May 1763 fifty-four of the leading citizens of Granville, Northampton, and Edgecombe Counties made a similar petition. They described their ‘Free Negro & Mulatto; neighbors as persons of Probity & good Demeanor [who] chearfully contribute towards the Discharge of every public Duty injoined them by Law.’”

“In March 1782 a Continental officer observed a scene in a local tavern at Williamsboro, North Carolina: ‘The first thing I saw on my Entrance was a Free Malatto and a White man seated on the Hearth, foot to foot, Playing all fours by firelight: a Dollar a Game.’”

“By 1790 free African Americans represented 1.7% of the free population of North Carolina, concentrated in the counties of Northampton, Halifax, Bertie, Craven, Granville, Robeson, and Hertford where they were about 5% of the free population…. In these counties most African American families were landowners, and several did exceptionally well.”

“The Bunch, Chavis and Gibson families owned slaves and acquired over 1,000 acres of land on both sides of the Roanoke River in present-day Northampton and Halifax counties, and the Gowen family acquired over 1,000 acres in Granville County.”

“William Chavis, a ‘Negro’ listed in the 8 October 1754 muster roll of Colonel William Eaton’s Granville County Regiment, owned over 1,000 acres of land, a lodging house frequented by whites, and 8 taxable slaves. His son Philip Chavis also owned over 1,000 acres of land, traveled between Granville, Northampton, and Robeson counties, and lived for a while in Craven County, South Carolina.”

“John Gibson, Gideon Gibson and Gibeon Chavis all married the daughters of prosperous white planters. Some members of the Gibson, Chavis, Bunch and Gowen families became resolutely white after several generations.”

“Some members of the Gibson family moved to South Carolina in 1731 where a member of the Commons House of Assembly complained that ‘several free colored men with their white wives had immigrated from Virginia.’ Governor Robert Johnson…summoned Gideon Gibson and his family to explain their presence there and after meeting him and his family reported, ‘I have had them before me in Council and upon Examination find that they are not Negroes nor Slaves but Free people, That the Father of them here is named Gideon Gibson and his Father was also free, I have been informed by a person who has lived in Virginia that this Gibson has lived there Several Years in good Repute and by his papers that he has produced before me that his transactions there have been very regular, That he has for several years paid Taxes for two tracts of Land and had several Negroes of his own, That he is a Carpenter by Trade and is come hither for the support of his Family.’”

“Many of the free African Americans who were counted in the census for South Carolina from 1790 to 1810 originated in Virginia or North Carolina” and, according to the surviving court records, included “at least three families [who] were the descendants of white slave owners who left slaves and plantations to their mixed-race children: Collins, Holman, and Pendarvis. James Pendarvis expanded his father’s holdings more than fourfold to 4,710 acres and 151 slaves. John Holman, Jr., established a plantation with 57 slaves on the Santee River in Georgetown District and then returned to his homeland in Rio Pongo, West Africa to resume the slave trading he learned from his English father,” thus becoming “probably the first and only African-born entrepreneur who resided in Africa as an absentee planter in the New World.”

In “Black Masters: The Misunderstood Slaveowners,” published in the Southern Quarterly in 2006, historian Larry Koger gives, among other examples, William Raper, born in the mid-1700s, “either freeborn or an emancipated slave,” who became “a bricklayer of Charleston City” and “provided the economic tools which helped establish one of the largest slaveowning families in St. Paul’s Parish in Colleton County.” By 1787, he owned ten slaves who had been “acquired as laborers”; he trained three as bricklayers. Raper’s will “requested that his daughter Ruth Gardiner should have the slave, John (the son of his slave, Tamer) after the death of his wife. He also provided his granddaughter Susan Elizabeth Gardiner with Tom, a skilled bricklayer, Tamer, and Bella.”

According to the 1790 census, another bricklayer, George Gardiner, who had once been a “commercial slave,” was listed at the time of his death in 1797 as the owner of seven slaves; he left them to his daughter. Koger explains, “During the late 1790s, many, if not the majority of free black slaveholding families held slaves to exploit their labor.” He concluded, “The southern experience of slavery was a diverse system not exclusively exploited by white Americans. Afro-American slaveowners also played a minor role in the saga of American Slavery.”

In the nineteenth century, as Heinegg recounts, “Many free African American families sold their land” and “headed west or remained in North Carolina as poor farm laborers,” “probably the consequence of a combination of deteriorating economic conditions and the restrictive ‘Free Negro Code,’” which was largely a reaction to Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion in nearby Southampton County, Virginia. John Hope Franklin described a series of restrictive laws passed from 1826 through the 1850s, wherein “[f]ree African Americans lost the right to vote and were required to obtain a license to carry a gun.”

The number of free blacks in the United States was 60,000 in 1790, nearly doubled in 1800, and then tripled in 1810 after the Louisiana Purchase. By 1830, there were 300,000 free blacks in the United States. Louisiana, specifically New Orleans, was one of the places with the best opportunities for free blacks, who “invested heavily in real estate and slaves.” As John W. Blassingame noted in his 1973 study Black New Orleans, 1860–1880, “Negroes” owned $2,214,020 worth of New Orleans real estate in 1850, much of it in the center of the city. Many “were successful as money lenders, real estate brokers, grocers, tailors, and general merchandising agents…. One of the best-known businesses was the import house operated by Cécée Macarthy, who inherited $12,000, which she increased to $155,000 by the time of her death in 1845. A free Negro undertaker, Pierre Casanave, relying on his predominantly white clientele, built a business valued at $100,000 in 1814.” In 1830, “735 Negro masters owned 5 or more slaves; and 23 Negro masters owned from 10 to 20 slaves.” A significant number held only “one or two slaves, usually members of their own families whom they often manumitted; such masters entered 501 of the 1,353 manumission petitions in the emancipation court between 1827 and 1851.”

Complex Relations

Race relations were complex in New Orleans. Free black men were required to serve as city guardsmen and to go “on slave patrols in the parishes to keep the peace.” In 1811, free persons of color were recognized for the significant role they had played in suppressing what amounted to the largest slave insurrection in United States history. New Orleans had the largest proportion of free persons of color of any city in the antebellum United States. Whatever the prejudices in New Orleans, a significant number of those persons surmounted barriers to become wealthy and successful. As a result, during Reconstruction, New Orleans blacks overall fared better than blacks in other places. Blassingame writes, “The role of blacks in [the] New Orleans economy . . .while restricted, still enabled them to compete successfully against whites in many areas after the war. Much of the black success…during Reconstruction was a direct result of the large number of highly skilled free Negro men in antebellum New Orleans.” Their wealth allowed them to form benevolent associations and found private schools.

In his first book, The Free Negro in North Carolina: 1790–1860, published in 1943, noted African American historian John Hope Franklin charted the status of the “Negro” in terms of population, legal rights, and economic and social life in a state that was “reportedly more liberal than most southern states.” Overwhelmingly, Franklin found, blacks fared poorly and were victims of discrimination, especially those who were enslaved.

Franklin claimed that “[t]he possession of slaves by free Negroes was the only type of personal property that was ever questioned during the ante-bellum period.” For a black man to acquire slaves and thus “improve his economic status” was seen by some “as a dangerous trend.” There was the question: “If the free Negro was not a full citizen, could he enjoy the same privileges of ownership and the protection of certain types of property that other citizens enjoyed? Around this question revolved a great deal of discussion at the beginning of the militant period of the anti-slavery movement.”

The 1833 North Carolina Supreme Court case State v. Edmund gave the answer in the affirmative: free blacks under North Carolina law were considered to be citizens with property rights that included the right to hold slaves. The decision, by Supreme Court judge Joseph Daniel, went for the black slave owner and against the black slave. The case involved a runaway slave named Edmund who had concealed his status and was working as a steward on a ship, where he hid another slave owned by a black man named Green. Edmund was imprisoned and was appealing his case. As Franklin explained, “[I]t was contended…that the prisoner, a slave, was not a person or mariner within the meaning of the act [of 1825] and that Green, the owner of the concealed slave, was a mulatto and hence not a citizen of the State and could not own slaves.” Judge Daniel, however, ruled, “By the laws of this State, a free man of color may own land and hold lands and personal property including slaves.” As Franklin commented, Judge Daniel was “well satisfied from the words of the act of the General Assembly that the Legislature meant to protect the slave property of every person who by the laws of the state are entitled to hold such property.” Daniel also wrote in his ruling, “The prisoner, although a slave, is a ‘person’ in the natural acceptation of that term; a slave is a person capable of committing crimes, and subject to punishment.”

“The decision of Judge Daniel remained the accepted view,” wrote Franklin—until “the hostility between the sections” developed “into open conflict” and “the free Negro in the South witnessed an almost complete abrogation of his rights.” This abrogation involved a law “passed during the momentous session of 1860–1861,” stating that “no free Negro, or free person of color shall be permitted or allowed to buy, purchase, or hire for any length of time any slave or slaves….” Admittedly, the number of slaves owned by blacks had been declining, as it had been among white slave owners. The law, however, “provided that free Negroes already possessing slave property would not be affected….” Franklin found that black slave owners usually held only one to three slaves. “[T]he petitions of free Negroes to manumit relatives suggest that a sizable number of slaves had been acquired” for that purpose. And most of “the free Negroes who owned property” possessed only “small estates.”

Yet there were “notable exceptions”—such as “the eleven slaves held by Samuel Johnston of Bertie County in 1790; the 44 slaves each owned by Gooden Bowen of Bladen County and John Walker of New Hanover County in 1830; and the 24 slaves owned by John Crichlon of Martin County in 1830.” Franklin names “several” free blacks who “amassed a considerable amount of property during their lifetime.”

One, Louis Sheridan, a slave owner, started “with a small store in Bladen County in the early years of the nineteenth century” and developed it into “a business that was among the largest in his section of the State.” His race seemed to have been no obstacle in making extensive “business connections with leading New York merchants” and, through former North Carolina governor John Owen, meeting “other influential men, including Arthur Tappan” (a white businessman, philanthropist, and abolitionist).

Sensing a coming clampdown on blacks, especially free blacks, after the “circulation of a ‘seditious’ pamphlet, Walker’s Appeal, by David Walker, a free black native of nearby Wilmington, and the outbreak of Nat Turner’s Slave Rebellion in Virginia in 1831, coupled with the rising tide of abolitionism in the North,” Sheridan looked to Liberia for opportunities for “full freedom and prosperity.” So he freed his slaves, “presumably on the condition they accompany him to Liberia,” sold his “enormous estate,” and emigrated to Liberia in 1837, where he set up business.

However, Sheridan was not happy in Liberia and wrote to Tappan back in America, complaining about the “peculiar barbarousness of this country and its yet more barbarous natives.” After Tappan released Sheridan’s letter, resistance to colonization arose. But Sheridan decided to stay in Liberia in order to fulfill his commitments to investors. He served on the Colonial Council and continued to serve after 1839, when “the American Colonization Society proclaimed the Commonwealth of Liberia…and appointed [Thomas] Buchanan, an old acquaintance of Sheridan’s, as governor.” After Buchanan’s death in 1841, Sheridan opposed the new governor, a “mulatto.” Sheridan died of an illness in 1844, having inspired “more hostility than admiration among his fellow Americo-Liberians,” whom he called “crazy,” and who, in turn, did not want to accept his exacting ways.

“Successful and Respectable”

In 1990, University of North Carolina–Greensboro history professor Loren Schweninger followed up on John Carruthers Stanly, the successful barber and son of an African mother and white father who had been featured in Calvin Dill Wilson’s 1912 article “Negroes Who Owned Slaves” (where his name was spelled “Stanley”). Schweninger published his story in a book, Black Property Owners in the South, 1790–1915, and in an article in the North Carolina Historical Review titled “John Carruthers Stanly and the Anomaly of Black Slaveholding.” As the title of Schweninger’s article indicates, black slaveholders were an “anomaly,” but they did exist. Stanly got his start when, as a slave, he was “hired out as an apprentice barber.” He learned the trade quickly, establishing his own barbershop in New Bern while still a bondsman. Stanly’s owners, convinced that he could support himself, freed him in 1798. By then he had expanded his business and was bringing on slave apprentices. He amassed a large number of slaves to work on his various properties as well as in his shop, and he was well respected and accepted by the white community. His family even had a pew in the white church. Stanly was referenced in an article written about the North Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1835, which argued against a proposal to deny free blacks the right to vote, on the grounds that it “would be highly unfair to the most successful and respectable members of this class, men like John C. Stanly of New Bern.”

Stanly built his wealth on slave labor. “Like his white neighbors, he became a regular bidder at slave auctions…. By 1820, Stanly had thirty-two slaves listed in his household in New Bern, including several who worked in his barbershop and as house servants.” Fifteen were children under the age of fourteen. “On his plantations he controlled another ninety-five blacks…. In all, Stanly controlled 127 blacks who were listed in the population census as residing in his household in New Bern or on one of his plantations.” At least one of the slaves he purchased was only two years old. He bought field hands usually as teenagers, but some were as young as nine. Even as restrictions were placed on “free Negroes” after “the abortive slave insurrection in neighboring South Carolina, led by the freed black Denmark Vesey, in 1822, and rumors of a similar plot in North Carolina,” Stanly maintained his position, buying more slaves to work under his three white overseers. By the late 1820s he had become “the largest slave owner in Craven County, and one of the largest in North Carolina.” Schweninger explains, “In his treatment of his bondspeople, Stanly differed little from his white neighbors. One New Bern resident, Colonel John D. Whitford, recalled that Stanly was a ‘hard task-master’ who demanded long hours in the fields and ‘fed and clothed indifferently.’” The record suggests “that Stanly would have few pangs of conscience about selling a slave away from his parents.” By 1860 his net worth far exceeded the average for white Southerners, which was less than $4,000. Schweninger explains, “Stanly’s $21,200 worth of real property would have placed him in the top one half of one percent among white men in the nation at midcentury; and his 1820s total estate was seventeen times the average for southern whites…on the eve of the Civil War.” Ironically, his fortunes took a temporary downturn when he backed a loan for his white half brother.

Schweninger notes a surprising fact: in 1838 Stanly “wrote the American Colonization Society in behalf of Lott Holton, an elderly man” who wanted to emancipate seventeen young slaves and send them to Africa. “Whatever happened to the seventeen slaves was not revealed in the record, but the paradox of a free Negro slaveholder who continued to hold his own slaves seeking to assist a white slaveholder in ‘returning’ his slaves to Africa symbolized the ambiguous nature of blacks holding their brethren in bondage.”

Black plantation owner Andrew Durnford regularly communicated with a white man, John McDonogh, who acted as his agent in buying slaves. In an article in Louisiana History, David O. Whitten reproduces Durnford’s correspondence regarding transactions in the 1830s. Slaves were notated only by first name and age, along with the amount paid and shipping costs. Whitten comments, “The letters presented here transmit the tone of a neglected aspect of the domestic slave trade, the attitudes of a black man on the enslavement of his race, and general obstacles encountered in transporting coffles [groups of slaves chained together] from the old to the new slave states.” McDonogh became a vice president of the American Colonization Society and “shipped eighty-five freed slaves to Liberia in the 1840s.” In his will, he “left a large bequest to the society” and “provided for the emancipation of most of his remaining slaves for shipment to Liberia.” McDonogh’s correspondence with Durnford, Whitten notes, exposes “the apparent paradox of a black slave owner on a slave buying expedition being entertained by a white abolitionist.”

Other free blacks in North Carolina prospered. In the 1860 census, John Hope Franklin found “fifty-three free Negroes who possessed more than $2,500 worth of property,” including Jesse Freeman of Richmond County ($20,300), James D. Sampson of New Hanover County (over $36,000), Hardy Bell of Robeson County ($14,000), and Lydia Mangum of Wake County ($20,816). Sampson was one of the free Negroes who “experienced little difficulty in securing employment in North Carolina in the building trades” during the antebellum boom times, despite protestations by white workers. He became a “respected and wealthy citizen of Wilmington” through “his own industry as a carpenter” and shrewd investment in real estate. Franklin counted Sampson as among those in antebellum North Carolina “who were not only satisfied with their own position but with the general structure of North Carolina society as well.” He quoted an editorial in the Fayetteville Observer lauding the conduct of the “slaves and other colored population,” and a letter by “a prominent New Bern citizen in 1854” that praised “the displays made by” the “elegantly” dressed “Negro Elite” on Sundays at the Episcopal church. That letter noted that “a large number of [the] young men and several of our merchants” had “negro wives or ‘misses’ and [kept] them openly, raising up families of mullatoes.”

The situation was similar in South Carolina, as Larry Koger and Carter Woodson before him observed. The “artisan class” of urban “free Negroes” faced less discrimination than they did in the North. That was especially true in Charleston, where they comprised “[a] large portion of the leading mechanics, fashionable tailors, shoe manufacturers, and mantua-makers,” wrote Woodson in 1922. As we have seen, some launched themselves into the class of the wealthy. Class distinctions had been established by 1820, and elite slaveholding blacks like Jehu Jones were certainly tolerated—even well liked, if not fully accepted—by white society. “Many within the white aristocracy,” Koger states, “viewed the elite community of Afro-Americans as a safe class of people who understood the virtue of slavery and protected the southern system of labor.” For example, an editorial in the December 9, 1835, Charleston Courier praised the conduct of the local free blacks as “for the most part so correct, evincing so much civility, subordination, industry and propriety, that unless their conduct should change for the worse, or some stern necessity demand it, we are unwilling to see them deprived of those immunities which they have enjoyed for centuries without the slightest detriment to the commonwealth.”

Racial boundaries were also weak when it came to the impoverished. Poor and orphaned children of both races were “bound out until the age of twenty-one by the county courts.” In New York City, both white and black people of means set up philanthropic organizations and orphanages for such black children. Free blacks often sought to distinguish themselves from slaves and former slaves. They resisted forced integration with the formerly enslaved in schools during Reconstruction. Heinegg recounts that “Hamilton McMillan, a Democrat from Robeson County, took advantage of the fact that the African Americans who had been free since colonial times resented the loss of status they experienced when they had to attend the ‘Colored’ schools with the former slaves. In order to secure their votes for the Democrats, he helped pass a law which allowed them to have their own separate schools.”

The class division evident in such places as New York City, where an established and wealthy group of free blacks lived in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, carried through into the twentieth century. Harlem became a thriving black mecca largely through the efforts of enterprising black real estate investors who saw an opportunity in the overbuilding by whites. They sold and rented to blacks, driving out whites, and then charged high rents to blacks. In his autobiography, George Schuyler described how long-established black Yankee families shunned black migrants coming north to Syracuse, New York, where he grew up at the turn of the twentieth century. A Dr. Dumas of Louisiana (a “distinguished” “mulatto”), who had inherited his wealth from plantation-owning forebears who had built their wealth with slave labor, helped Schuyler on his reporting forays through the South in the 1920s and 1930s.

Anecdotes of black slave ownership abound, but since at least 1922, when Carter G. Woodson scoured census records for his groundbreaking Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States in 1830, scholars have also tried to quantify levels of ownership. According to two Canadian researchers, Woodson misinterpreted those records in part and, as a result, overestimated the number of slaves owned by blacks for benevolent purposes. David L. Lightner and Alexander M. Ragan reexamined the evidence and published their findings in the Journal of Southern History in 2005. “Woodson’s claim,” they wrote, “appears plausible, for there were indeed many impediments to manumission in the South— and thus many reasons for blacks to own relatives and loved ones rather than buy them and then simply set them free.”

By the antebellum period, free blacks were also burdened with annual registrations and fees, as well as higher poll taxes and fines, under the threat of temporary bondage for nonpayment. In order to practice in their limited number of trades they had to purchase expensive badges and licenses. And, Lightner and Ragan concede, though the biographies of four black slave owners—John Stanly (covered in “John Carruthers Stanly and the Anomaly of Black Slaveholding” and Black Property Owners in the South, 1790–1915, both by Loren Schweninger), Andrew Durnford (David O. Whitten, Andrew Durnford: A Black Sugar Planter in the Antebellum South and “Slave Buying in 1835 Virginia as Revealed by Letters of a Louisiana Negro Sugar Planter”), William Ellison (the subject of Michael P. Johnson and James L. Roark’s Black Masters: A Free Family of Color in the Old South, 1984), and William Johnson (The Barber of Natchez by Edwin Adams Davis and William Ransom Hogan, 1954),—are “arresting,” they “provide no indication of what proportion of black slaveholders were similarly exploitative.”

The “most powerful challenge” to Woodson’s high estimate of the proportion of slaves who were owned by free blacks for benevolent reasons, Lightner and Ragan assert, comes from Larry Koger’s 1985 Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790–1860. The research of Koger, whose account of the free black bricklayer William Raper we discussed above, included “exhaustive research in census returns, tax lists, legal documents, business directories, newspaper accounts, and other sources.” Lightner and Ragan reexamined the raw census data used by Woodson in his 1924 book and corrected the errors pointed out by Koger. They found that correct comparisons between white slaveholders and black slaveholders showed that “slave owning was fairly widespread among the free black population.” The 3,699 black slave owners constituted “almost exactly 2 percent of 182,070, the total of free black population of the South.” Admitting that the number may appear small, they point out that it is actually a significant proportion, given “the small percentage of the total white population who were slaveholders,” 223,898 out of a total population of 3,660,758—or “almost exactly 6 percent.” In fact, going by the census data, “a southern white was just three times more likely to own slaves than was a southern free black”—a finding “more striking” in light of the fact that there was a “substantial undercount of black slave owners.” And on a national level, “a white American was not even twice as likely as a free black American to be a slaveholder in 1830,” given the fact that the majority of whites lived in the North.

Lightner and Ragan’s estimates are conservative. They worked from the assumption that all the black slave owners who owned only a small number of slaves were benevolent, whereas in reality there must have been some who owned one or two slaves for exploitative purposes. They conclude that “Woodson was correct when he said that the majority of black slaveholders were motivated by benevolence,” though the number of exploitative slave owners was “more substantial and their slaveholdings far more significant than Woodson implied.”

As Koger and others have pointed out, just as some slaves were treated harshly and even viciously by some white slave owners, the same was true of some black slave owners. The race of the owner did not determine how slaves were treated.

Created Equal

Alas, slaves, by virtue of their status, were at the mercy of their owners. A Frenchman traveling through the sugar country of Louisiana in 1803 observed that among the Creole planters the “fine feelings of humanity are quiescent or dead as far as the slaves are concerned” and that slaves worked “the land, like a mule, like an ox.” An “organized service of overseers, leaders, watchmen…with whips in their hands” were ready to punish—but with only “a few lashes or days in the dungeon,” so as not to lose valuable workers.

But attitudes changed. In 1776, Americans declared that “all men are created equal.” And then they fought a Revolution in pursuit of that idea. This new notion spread across the globe, including to a tobacco plantation in Maryland, where in 1803 an overseer decided to quit his lucrative position because of the new difficulties of his job. James Eagle wrote to his boss, “I am now drawing towards 50 years of age I have spent 21 of that time on this place the first part of it much more agreeable than the latter.” In Lorena Walsh’s article “Slave Life, Slave Society, and Tobacco Production in the Tidewater Chesapeake, 1620–1820,” she explains, “The slaves he supervised had decided they, too, had an inalienable right to freedom. Eagle found ‘they Get much more Dissatisfied Every year & troublesome for they say that they all ought all to be at there liberty & they think that I am the Cause that they are not.’” Their behavior had changed: they gave him so much “trouble” that half the time the overseer was in “hot blood” and unable to “[c]onduct my business as I ought to do.”

Thomas Jefferson may not have freed his slaves in the manner and time frame his critics demand centuries later, but his words helped set in motion a new philosophy that had worldwide repercussions. As Ira Berlin has noted, “Prior to the American Revolution and its idea of universal equality, there were few [abolitionist] movements to contemplate, let alone to join.” When blacks filed suits for freedom—as they did, for example, in Connecticut in 1779—they used the language of the Declaration of Independence.

Click here to learn more about the book.

MORE: In defense of Prof. Grundy: There’s a good chance she never learned black people owned slaves

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.